Typically the reserve of 100-year-old commodity houses, the mining industry is suddenly gaining the attention of a new group: tech startups and their investors.

They’re betting that AI can revolutionise the age-old sector and, in doing so, shore up the world’s supply of critical metals needed for the green transition, such as lithium, copper, nickel and graphite.

“Many mainstream VCs are looking at this space, and not just climate VCs,” says Olivia Brooks, head of investments at Founders Factory, which runs a mining tech accelerator alongside Rio Tinto. “I’ve spoken to funds that would ordinarily invest in B2B SaaS, and they’re looking at mining technologies now.”

“The mining sector is on the verge of a major technological shift, driven by the growing demand for critical minerals that power renewable energy and electric vehicles,” says Gem Jua, investor at climate-focused VC firm Rockstart.

It’s a trend that, according to funding data, has popped up in the last two years — defying the wider cooling in tech investment seen across that period. 2023 was a record year for Europe’s mining tech industry, with startups bringing in just over half a billion dollars, according to Dealroom.

Earlier this month, California-based Kobold Metals raised the sector’s largest round so far: a $537m Series C to exploit a copper deposit in Zambia that it found using AI. The round signalled investors’ growing interest in the category and pushed Kobold’s valuation to $3bn.

Scroll to the bottom of the article for a full list of European startups working on mining technology.

Risks and hurdles

Despite the interest, not everyone is convinced European startups can get in on the trend. Andy Schwarzenbrunner, general partner at early-stage VC Speedinvest, says he still sees a hesitancy around mining in Europe.

“It’s a pity because it is greatly needed for European sovereignty,” he says. “When you consider that the mining industry turned over over $2tn in 2022 alone, the lack of interest and activity is even harder to understand.”

Challenges remain. For one, the market is dominated by a few large mining conglomerates that “can decide who wins the race,” Schwarzenbrunner says. Another hurdle is the availability of relevant data sets, which Schwarzenbrunner says are often non-digital and sometimes lost altogether.

Jua points out that developing new mines is a lengthy process (often taking 5 -15 years) with delays stemming permitting and regulatory hurdles.

“This coupled with rising interest rates and limited financing options, could constrain the ability to fund exploration and new developments,” Jua says — though he notes that that also makes a case for more tech-driven exploration.

All that said, there’s a cohort of plucky European startups going up against the challenges — we’ve mapped them below.

Exploration startups: the software

The first step to mining a metal is finding it. Geologists do so by assessing maps and taking samples; exploration startups, like California’s Kobold, are developing algorithms to help.

Founders Factory’s Brooks says exploration is the busiest and best-funded part of the mining value chain. Rockstart’s Jua agrees: “Tech-driven approaches, like AI-powered geophysical surveys, are leading the charge.”

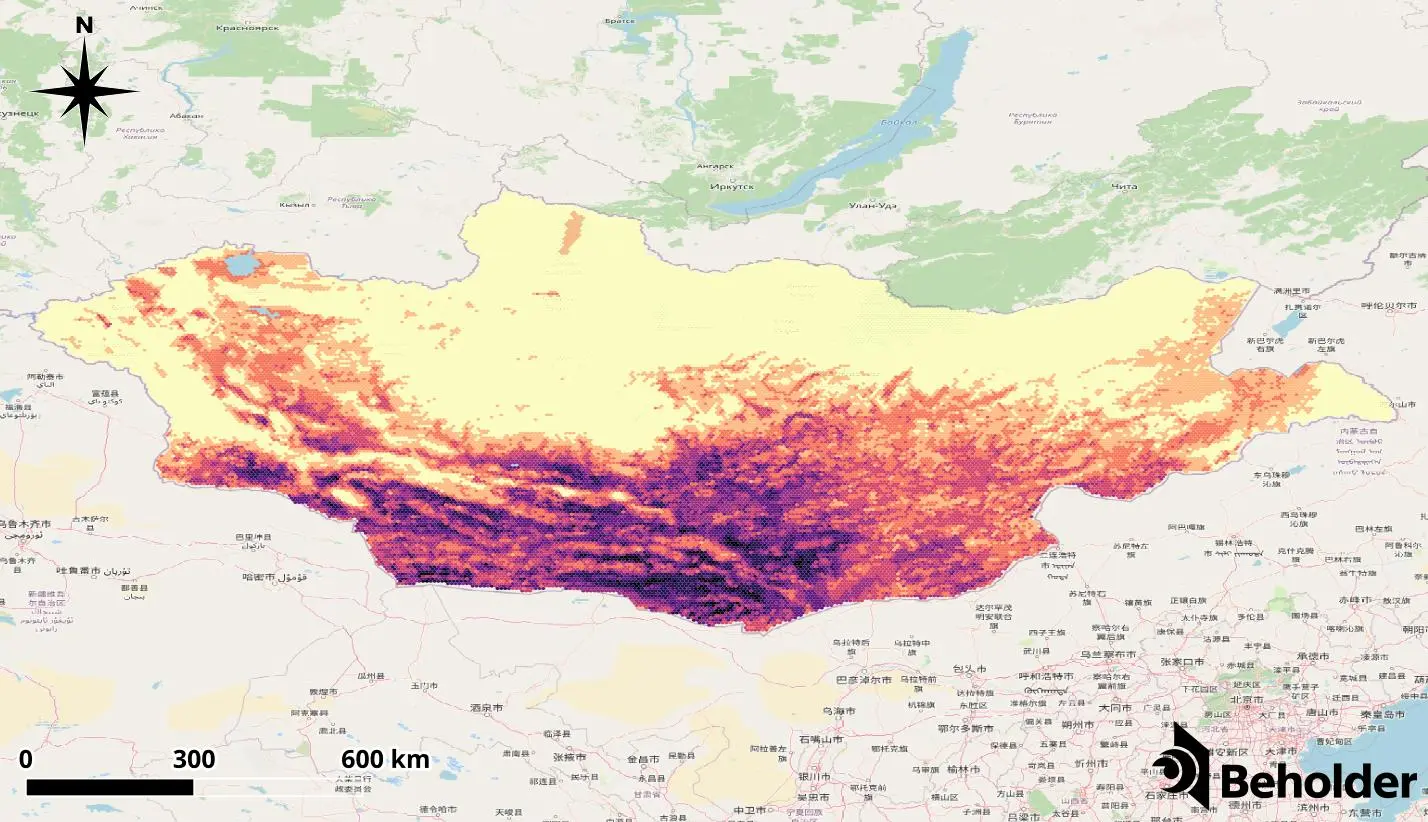

European startups working on exploration software include Ukrainian startup Beholder, which uses AI to access satellite images and geological data to predict where metals are. It can turn measurements of the Earth’s surface into a 3D map of the ground beneath a certain site.

“We can save companies’ money on exploration and lower the uncertainty they face before they start to drill,” says Daniil Lubkin, COO at Beholder, which is working on tech to find nickel, aluminum, copper and gold.

Exploration startups’ business models differ. Kobold owns the copper deposit it found and has raised funding to mine it, while others sell their tech to mining companies. Beholder takes stakes in the companies it sells its tech to, as a form of part-payment.

Exploration startups: the hardware

As well as exploration startups working on algorithms, there are those working on data collection tools.

ProSpectral, a Cambridge University spinout, for example, is developing a camera which records spectral data — information that can help detect materials. The camera is deployed on drones and satellites.

Birmingham University spinout Delta G is also working on exploration hardware. Its tool measures subtle changes in gravitational fields when clouds of atoms are dropped. That allows it to survey complex landscapes, detecting where metals could lie.

Precision mining startups

Once a deposit is located, the next task is getting it out of the ground: a process that can be extremely invasive, involving diggers and large pits.

“With sustainability now at the forefront, there’s also an obvious demand for methods that minimise environmental impact, reducing pollution and deforestation,” says Rockstart’s Kua.

Startups are working on ways to extract ore — the raw material containing metal — from the ground with more precision.

Thunderstone, a soon-to-be-spinout of London venture studio Deep Science Ventures, for example, is using electricity to create channels in the ore, then removing only the desired metals through engineered pathways, eliminating the need to disturb vast amounts of rock.

“This method could eliminate the need for disturbing thousands of square kms of land currently affected by conventional mining practices,” says founder Eric Burns.

Extraction startups

Once ore is removed from the ground, the next task is extracting metal from it. Startups are working on ways to make that process greener or increase the yield.

There’s Swedish startup Green14, for example, which uses green hydrogen to separate silicon and oxygen from quartz, instead of using coal.

There’s a subset of extraction startups working on recovering metal from ‘mine tailings’: the materials left over from the initial extraction process. US startup Endolith, for example, uses microbes to extract copper from mine tailings, hoping to reduce the industry’s waste.

Synthetic alternatives

Critical minerals needed for the green transition are in short supply. That’s ushering in a new cohort of companies, adjacent to mining technology: those working on developing synthetic alternatives to metals. Startups are either doing that in the lab or using AI to come up with new recipes.

Oxford-based startup Milvus Advanced, for example, is working on transforming cheap, common metals into materials that can be used in the place of precious metals in things like solar panels. The company’s backed by Lowercarbon Capital and Unruly Ventures.

All of Europe’s mining startups:

Read the orginal article: https://sifted.eu/articles/vc-mining-tech-startups/