Jan Goetz, the CEO of Finnish-German startup IQM Quantum Computers, has a bold vision: to be the “European answer to the Googles, IBMs, Fujitsus and Huaweis when it comes to quantum.”

The seven-year old company has a two-pronged approach to achieving its chief’s ambition. One side of its business builds full-stack, superconducting quantum computers and manufactures the chips to put in them; the other sells quantum compute time through the cloud.

“We’re focusing on building the most performant quantum processers when it comes to speed, quality and stability, “ Goetz tells Sifted.

Companies around the world are racing to be the leader in quantum computing, which has the potential to solve problems beyond the reach of classic computers. Governments are showing a strategic interest too. France, Germany and the UK have announced billion euro national quantum packages in the last four years.

Big Tech has upped the ante for the quantum industry recently. Google unveiled a 105-qubit chip, ‘Willow’, in December, and Microsoft announced a quantum ‘breakthrough’ in February.

But IQM isn’t just up against the weighty cheque writing ability of much larger quantum players. It’s also competing with European startups such as French company Pasqal and British startup Oxford Quantum Circuits, which are also building full-stack systems.

So can it compete?

Chasing qubits

Quantum computers can’t currently do a lot: the limited size of quantum processors and high error rates significantly limit their power. To overcome these problems, companies are racing to create devices with more qubits — the quantum equivalent of bits in a normal computer — as well as using different types of qubits and developing error-mitigating techniques.

IQM has two models of quantum computer which it builds, ships to customers directly and installs on site.

Radiance is a 54-qubit quantum computer which IQM sells to large supercomputing centres for up to €30m. This year, it will launch a 150-qubit version which it will use internally. By the end of 2026, it wants to deliver the system to its first customer, Leibniz Superconducting Centre.

As a comparison, French company Pasqal, which uses a particular type of qubits called neutral atoms, sells quantum processors with 100 qubits. It also sold a 200 qubit quantum computer to Saudi oil and gas giant Aramco in 2024, which is set to be deployed in Saudi Arabia in the second half of 2025.

Spark is IQM’s five-qubit quantum computer, which is sold to universities and research labs for up to €20m. It’s used to help students learn how to use a quantum computer and carry out research experiments. A recent customer is the Taiwan Semiconductor Research Institute (TSRI).

IQM has also sought out corporate partnerships — which are becoming increasingly important for quantum companies to get their tech out into the market. For example, any customer which uses one of IQM’s quantum computers gets access to CUDA Quantum: US chip designer Nvidia’s open-source programming model for hybrid quantum-classical computing.

“It’s important for us that our computers will be used in the end, right? We don’t just want to sell something and it become a museum piece,” says Goetz.

Other revenue streams

A key consideration for quantum startups selling hardware is how to make money while the technology, and its use cases, are still being developed.

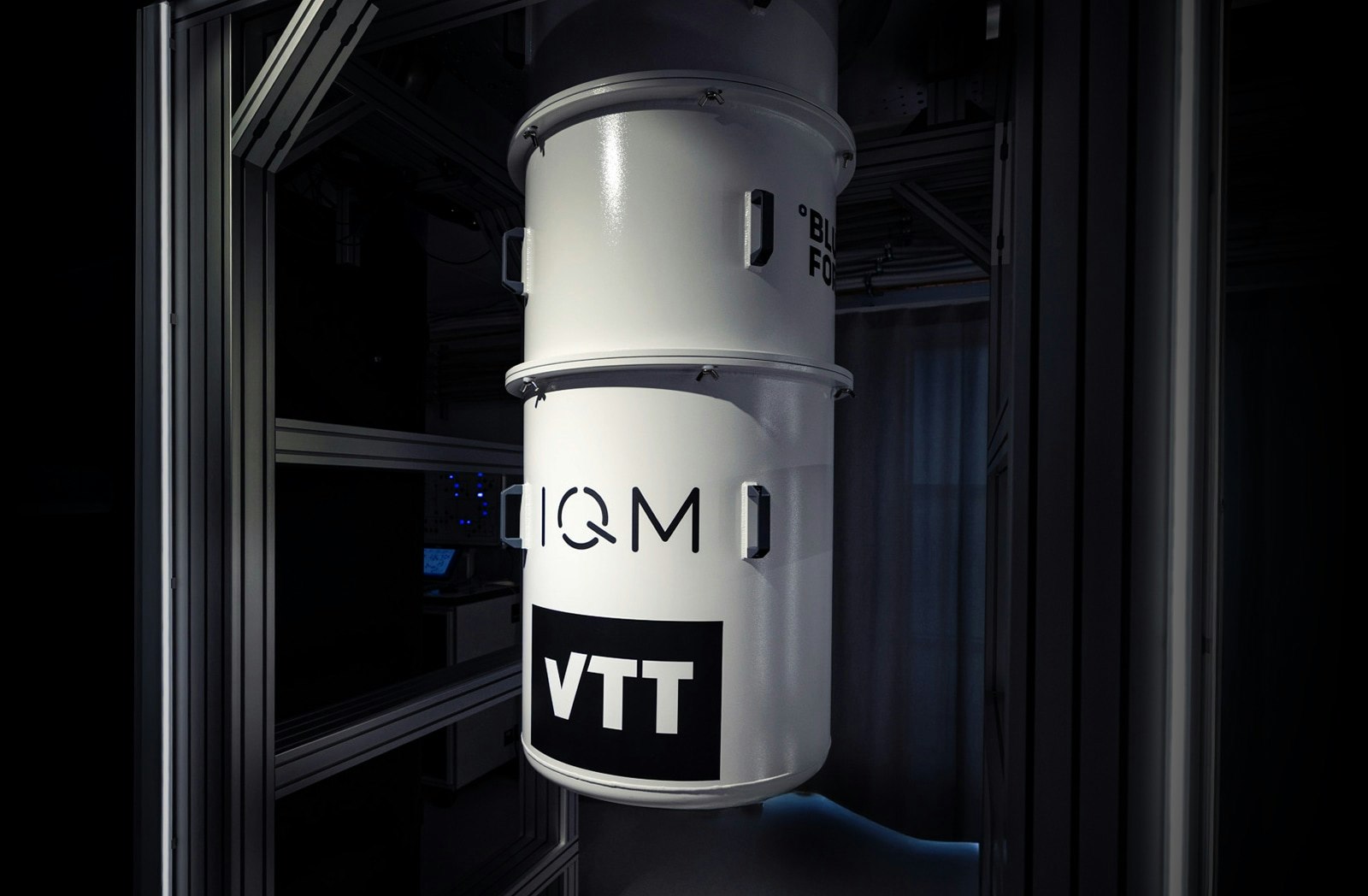

Aside from selling quantum computers, IQM makes money by running two quantum data centres — one in Finland and one in Germany — and selling compute time to customers through the cloud on a pay-as-you-go basis.

The company also makes money by charging customers 10-20% of the cost of the computer for maintenance — which they pay in one lump sum or on a monthly subscription basis. Additionally, it offers training to customers so they can do the maintenance themselves — a particularly sought-after option for companies working in sensitive areas that require high security, says Goetz.

IQM has so far sold 13 quantum computers to clients across Europe and Asia, and is beginning to sell to the US, where it could imagine building its own production lines one day, says Goetz. The company declined to provide information on revenue or margins, but said it will reach profitability “a couple of years from now”.

It’s important for us that our computers will be used in the end, right? We don’t just want to sell something and it become a museum piece.

The company produces quantum chips for its computers in its own private chip factory in Espoo, Finland, which currently has capacity to produce up to 20 quantum computers per year. Goetz tells Sifted that IQM hasn’t ruled out eventually producing chips for other companies, but that it is not currently in the company’s roadmap.

“It requires a different level of maturity,” he says. “A lot must happen before quantum is a volume business […] at the moment there is no good business model for specialised chip makers.”

All of this has been enough for investors to pump $210m into IQM since Goetz cofounded the company with Mikko Möttönen, Kuan Yen Tan and Juha Vartiainen in 2018. Its cap table is a mixture of VC, venture loans from the European Investment Bank and public funding from Finnish state-owned investor Tesi and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

Scaling up

One of the major challenges that may stand in IQM’s way from competing with Big Tech is capital; raising at Series B and above is a well-known challenge in Europe.

Some of IQM’s US competitors have raised much larger sums of capital. PsiQuantum, for instance — which differs from IQM in that it builds photon-based quantum computers — has raised $1.6bn to date, according to Dealroom data.

“As a deeptech company we are always fundraising,” says Goetz. “We have a clear path to profitability, but until then we need to raise money to scale up which means we are subject to market fluctuation.

“And the question is, is there enough capital to carry us forward all the way to profitability?”

Another roadblock to scaling could be the quantum talent crunch given the industry in Europe is still nascent.

“There’s already a shortage now, and we expect that it’s going to be much tougher once the industry is having the AI moment,” says Goetz. IQM currently employs 300 people across Germany and Finland.

One way of potentially getting around the talent crunch is by partnering with universities. IQM co-operates a 5-qubit quantum computer with VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland; some of its employees are also doing their PhDs at local universities in Finland, says Goetz.

Another way is training up tech workers in quantum physics from other industries, like semiconducting or AI. IQM has its own online academy to encourage students and other professionals to learn the basics of quantum computing to help get more quantum talent into the pipeline.

Money and a ‘Big Tech’ brand isn’t all it takes to attract good talent and deliver a good product in Goetz’s view, and he says that IQM’s appeal is that it can move much faster than Big Tech.

“We are just transitioning from 54 to 150 qubits. We started [on quantum] five years later [than Google], so we have been running basically twice as fast. And this clearly shows that as a young, agile company, you can be competitive.”

Read the orginal article: https://sifted.eu/articles/iqm-quantum-taking-on-big-tech/