When Berlin-based startup founder Jérôme Bau set out to change his company’s address, he didn’t expect that it would take several weeks to do so.

The wad of paperwork he had to fill out from the District Office in a country where fax machines largely prevail wasn’t a surprise, but the sheer length of time to change an address within the same city? That was absurd.

For Bau, the process of changing his company’s address went like this: he had to go to an appointment at the notary where a staff member read aloud that an address change was going to take place; he then signed the document in wet ink. He then had to wait a few weeks for the commercial register to approve it, he explains.

The process didn’t stop there. After informing the German tax office of the change in address, Bau forgot to do the last step of notifying the district office, he admits. He ended up receiving “angry letters” from the district office for a year.

“This is just one example of a million processes where there is friction,” says Bau, whose startup uses AI-powered role plays to train sales and customer service teams.

Everything I do as a founder, when it comes to formalities, feels like I’m building a factory for metalworking in the 1800s

“Everything I do as a founder, when it comes to formalities, feels like I’m building a factory for metalworking in the 1800s,” he adds. “I go to notaries, there’s a lot of paper, nothing is digital. There are things taped together. It all feels very ancient.”

German bureaucracy in action

For many startups, brushing up against bureaucratic hurdles is a weekly, if not daily, occurrence in Germany. Registering a company can take anywhere from five weeks to more than five months depending on who you ask; as a comparison, it takes less than 24 hours in the UK. Meanwhile, founders say accounting, payroll and even receiving investment in Germany is nightmarish.

According to the KfW 2024 Startup Monitor, bureaucracy is the most common obstacle for founders which, in some cases, can lead to individuals abandoning their plans to start a business, the report notes.

Founders’ qualms about bureaucracy are significant for a country that is eager to cement its position as a top startup hub and encourage world-class companies to be built in Germany.

Earlier in September, the German Startup Association revealed its “Innovation Agenda 2030” — a set of goals to support the growth of German startups and make the country a more attractive place to start a business — and easing bureaucracy via digitalisation was one of the top priorities mentioned.

“Almost 90% of all founders see the acceleration and simplification of administrative processes as a key lever for further developing the startup ecosystem,” Verena Pausder, chairperson of the German Startup Association, told Sifted.

“While elsewhere you can set up and manage companies completely digitally, in Germany you often have to wait weeks or even months just for the tax number or VAT ID. Estonia shows with its ‘e-Residency’ programme that this is possible fully automatically and immediately.”

The association wants to streamline the process of starting a business by creating a “one-stop shop” that bundles all the necessary applications together with online support services so that companies can be built in a day. It also called for the government to hire a chief digital officer with extensive powers in the federal chancellery to centrally coordinate and accelerate digitisation projects.

“A constant stream of complicated things”

Bureaucracy is arguably harder for international founders who are often, at first, less acquainted with how things work in Germany, and find grasping German legalese tough.

“I find it hard to imagine how I could run a German startup without a German cofounder because there is so much bureaucracy to deal with on an almost daily, at least weekly and definitely monthly basis,” says Steven Renwick, the UK-born cofounder of Tilores based in Berlin.

It feels like there is a constant stream of fairly complicated things that are, of course, in German, which you need to be dealing with

“It feels like there is a constant stream of fairly complicated things that are, of course, in German, which you need to be dealing with.”

One of those “complicated things” is accounting.

Renwick says that when he had a startup in the UK, it wasn’t necessary to employ accountants on a regular basis, other than once a year for doing a VAT return, as corporation tax and payroll were able to be done easily by the company itself. “There is no way you could do that on your own in Germany,” he says.

Renwick pays accountants on a monthly basis to do bookkeeping, including payroll, which costs three to four times as much as it does in the UK, he adds.

Other things that cause stress for founders include waiting weeks for a tax number to arrive in the post so that the company can start paying invoices. Founders often have to start their companies months before they intend to start selling anything just to leave time to receive their tax number, according to Bau.

“In a digital age, there’s no reason it should take longer than a minute [to receive a tax number] and it takes weeks,” he says.

Establishing company entities elsewhere

Struggles with bureaucracy have led some founders to legally establish their businesses in other countries such as Estonia, the Netherlands or the UK while being registered as a resident in Germany, as the process of doing so is smoother.

Ananta Vangmai, the Berlin-based founder of battery-recycling company ReviveBattery, was given a week to incorporate her company — something that would be impossible to do in Germany — after receiving a grant from Google, and ended up incorporating in the Netherlands, which took two days.

In Germany, she’d already spent two months trying to find the right notary to set up a company and filling out paperwork which was “a nightmare”, she says, especially as a neurodiverse person with a brain that functions and takes in information in a different way from someone who is “neurotypical”.

Founders in Germany also have to deal with a lot of bureaucracy in their personal lives, such as finding an apartment, filing taxes and sorting out health insurance, which only lumps more stress onto starting a business, says Vangmai, who is originally from India and grew up in Scotland.

“At the end of the day, entrepreneurs are human beings. If a human being is going to stress about the basics, the business is not going to flourish,” she says.

Dissuading investors

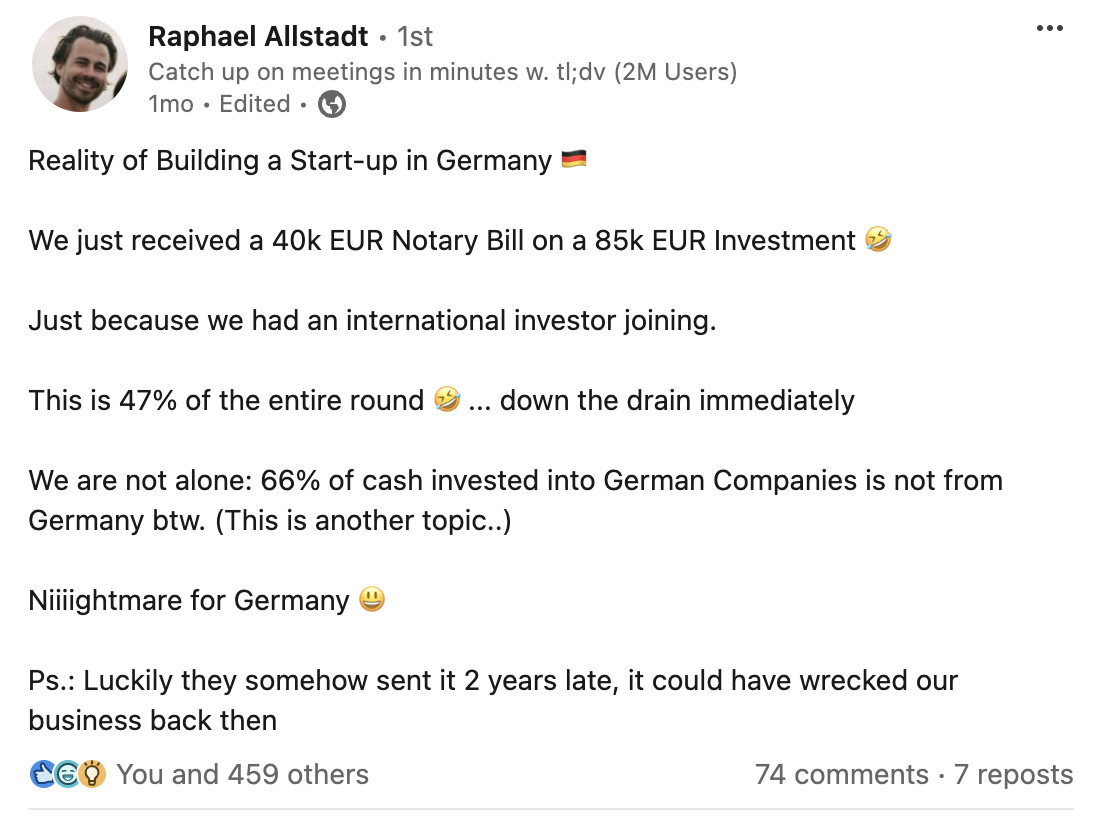

Setting up a company in Germany can be painful for founders, but many say receiving investment for it is even harder.

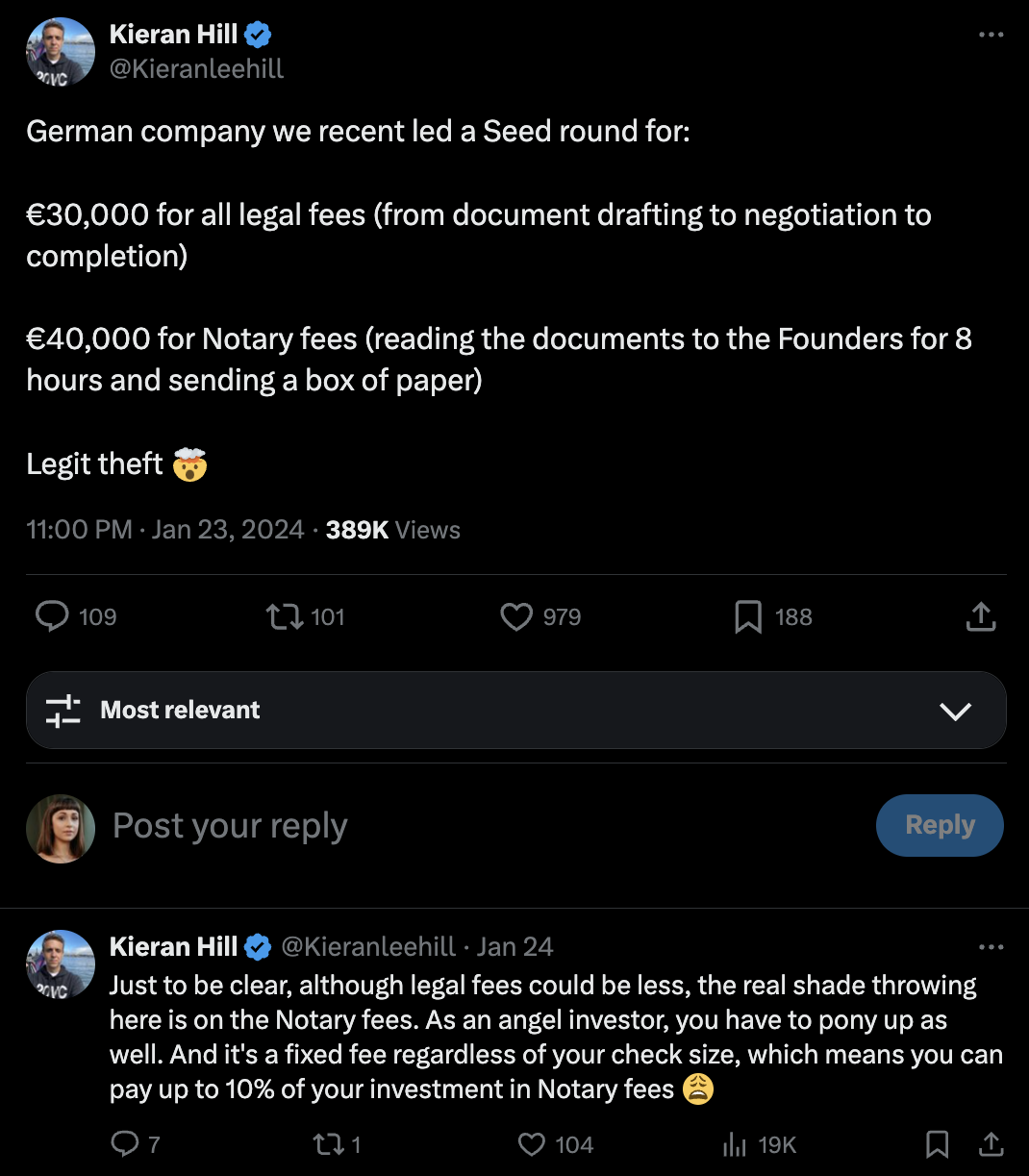

To complete a funding round as a GmbH, a German limited liability company, startup founders have to attend a notary in person with all of the investors (and their lawyers) present. If the investors cannot be present in real life, they have to give power of attorney to their lawyer or, in some cases, the founder. (Foreign investors have to provide a document proving they are giving power of attorney to someone, as well as an additional certification to prove that the notary in their own country is entitled to act as a notary in Germany.)

As with the address change saga, the notary reads the contract out aloud, checks through for any errors and allows for any negotiation between the parties to take place. The process can sometimes take as long as 10 hours if there is lots to discuss.

One startup lawyer tells Sifted that the positive side of the process is that it increases the chance that the investment documents are completely correct. Some founders, on the other hand, simply find it annoying.

“This is compared to an investment in a UK/US company where [investors] basically do an online Docusign investment and wire the money,” says Renwick. “That does have an impact as some investors will just refuse to invest in German companies. I had that experience myself.”

Signing off a contract at a notary can come at a high cost too, especially for the startup.

UK VC firm 20VC led a seed round of €2m for a German company earlier this year which cost the firm and the startup it was investing in a total of €30k in legal fees and €40k in notary fees.

“Companies already know they’re going to have to pay like €20-30k just to get their round over the line to the notary for their investors, so they already bake that into their cost base,” says 20VC partner Kieran Hill.

While the costs and fuss created for VC firms are vexing, it doesn’t make Hill “think twice” about investing in a top German company. Angel investors, on the other hand, are not incentivised to write cheques for German companies as the notary costs can cost up to 5-10% of the investment, he adds.

Some VC firms have already dreamed up ways to get around German bureaucracy and the associated costs. Renwick and Hill say that US investors often encourage German companies they want to invest in to transform into a US company form — such as a Delaware LLC (limited liability company) — so that they can avoid the tangle of German processes and manage the company from the US side.

Renwick says he can’t imagine it’s a good thing for Germany if companies born in the country want to transfer to an international company form.

“The pain of setting up a German company and of receiving investment affects Germany’s competitiveness because many people who have had a German company and have exited don’t want to go through that again,” he adds.

“If I were to set up another company, I’d set up a UK limited [entity].”

Why Germany?

So if it is so hard to start and run a company in Germany, why do founders do it?

The sheer market size of Germany is one thing, founders tell Sifted, as are the high number of grants and corporate startup incubators and the quality of the talent, particularly engineers and developers.

Bureaucracy isn’t just a German problem either, but a European one, says Hill.

“I think Europe has a fragmentation and regulatory issue more generally,” he says. In the UK, for example, trying to set up a fintech and get a licence to become a bank “can take months and kill a business before it’s even started”.

Still if Germany is to attract international talent, create world-leading companies and compete as a startup nation it has to be open to change.

“Germany is so far behind in terms of technology,” says Vangmai. “For Germany to really get with the times, it needs to loosen up in terms of paperwork, digitise a lot of things and make English a second language.”

That would also help to make the country more open and accommodating for international founders.

“Germany does not give space for an immigrant to give the best of their creativity and skills,” says Vangmai.

“We can bring our creative thinking into solving the problems we have here. We just need the government to acknowledge it and give us the empathy and the space to make [starting and running a business] possible.”

Read the orginal article: https://sifted.eu/articles/german-founders-battle-bureaucracy/