With the unfolding phenomenon of SpaceX’s Starlink rollout having caused a pronounced stir in the satellite market, the industry has been eager for clues as to how the emergence of another big tech Low Earth Orbit (LEO) giant in Amazon’s Kuiper Project could shake things up further as it rolls out this year.

Kuiper’s initial constellation is intended to contain 3,236 satellites weighing around 600kg each, with a solar array spanning eight meters and costing up to $2 million per satellite to manufacture – heftier than Starlink’s 260kg models which also sport a similar-sized array – delivering broadband through three consumer and commercial terminals capable of speeds of 100Mbps, 400Mbps, and 1Gbps at ruthless price points.

In total, the Kuiper fleet is intended to deliver 117Tbps when fully deployed, beating Starlink’s current capacity of 102Tbps, though it is likely Kuiper will always be playing catchup to Elon Musk’s company given that it also has plans for further deployments. Amazon claims its terminals will be hundreds of dollars below Starlink’s, which has a history of subsidizing its terminal prices to expand its customer base. Currently, Starlink clients have access to a network of more than 7,000 satellites.

Morgan Stanley estimates capital expenditure for the company on this work will amount to $96.4 billion in 2025 alone. Barclays estimates Kuiper’s revenue would represent $61bn by 2030, made up of $26bn in consumer segments and $25bn in business and enterprise such as data centers, as well as aviation and maritime connectivity. Reaching that outcome will depend on hitting rollout deadlines without any logistical or manufacturing surprises, as well as obtaining vital regulatory approvals.

First announced in 2019 and headed by Rajeev Badyal, the former vice president of Starlink, Kuiper launched its demonstrator satellites in December of 2023. Prior to this, in April 2022, Amazon announced contracts with launch providers Arianespace, Blue Origin, and ULA for up to 83 launches, which were due to begin in 2024. This has now been pushed back into 2025, and Kuiper expects to be able to deliver service later this year too, although this goal may prove optimistic. For reference, it took Starlink more than a year to build up enough capacity to guarantee commercial viability.

“Now that Kuiper is on the verge of its massive launch campaign, the satellite broadband business increasingly looks like a battle of titans, with the traditional players caught in the middle,” explains Caleb Henry, director of research at intelligence firm Quilty Space.

Amazon’s Kuiper team declined to comment to DCD on the ramifications of their entry into the satellite market.

The unfolding of the LEO era defined by these titanic entrants has influenced a string of mergers between the legacy satellite connectivity providers – many of whom are experts of more traditional geostationary satellites – such as Eutelsat merging with OneWeb, Viasat with Inmarsat, and most recently Eutelsat/OneWeb with SES.

These providers have seen success as innovative and intuitive connectivity partners with long-time relationships with their customers, who have often highlighted their differentiators in the face of faceless big-box offerings. Even so, in the face of big tech reliability, ubiquitous brand identity, and prices that border on the predatory, customers will be convinced, as many satellite operators themselves have been by the unbeatable price of launch with SpaceX Falcon 9.

Low-Earth advantage

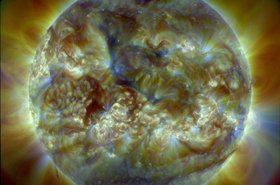

Closer to the surface of the planet, LEO satellites can deliver more throughput at the cost of the satellite’s effective reach. As demonstrated in a 1981 NASA mission headed by Sir Martin Sweeting, a service delivered by satellites in such close orbit required a network of models above all delivery areas on Earth simultaneously, making them unrealistic in the 1980s. Today, multiple companies sell LEO-based services, but few can claim to be a one-stop-shop for all connectivity needs.

While LEO broadband has, at times, outpaced terrestrial Internet services in certain regions, it is generally slower than fiber. But it remains a good option for rural and remote connectivity where cabled connections become impractical, as well as in developing nations. Sectors like military, aviation, and maritime, where connected assets are mobile in nature and often located far from urban hubs are natural anchor customers. It does hurt that military agencies also typically have considerable spending power.

LEO can also make up a hybrid network of mixed connections as a backup assuring more resilient networks, which is crucial for mission-critical applications and represents the most apparent advantage for most static data centers.

Tore Morten Olsen, president of maritime at Marlink, a network solutions provider for shipping, offshore, and remote markets, defines hybrid networks as the solution of choice for maritime and energy users. “LEO works well within a hybrid network because it enables high bandwidth and low latency applications that can be harder to achieve over VSAT without major bandwidth commitments,” he tells DCD. “Demand for LEO connectivity is growing very strongly in maritime because it is a market that until recently has been a somewhat underserved niche. With the exception of operators of large and sophisticated vessels, most shipping companies have traditionally made little outlay on digital solutions but that is changing, not least due to LEO.”

With 100,000 vessels in the world, many still using very basic communications, easy-installation LEO serving business needs and crew welfare has a lot of room to grow.

How big is Starlink’s lead?

With a total of 12,000 satellites planned to enter the Starlink constellation and paperwork filed to regulators for 30,000 more, Musk’s service has the numbers advantage, though quantity may not be the sole ingredient for success.

Experts have claimed Starlink’s fascination with vertical integration could prevent symbiotic technological relationships, distancing the company from enterprise and government needs as well as the associated regulatory frameworks.

“Starlink will certainly not be the gold standard,” argues Ronald van der Breggen, chief commercial officer at Rivada Space Networks, a competing satellite network provider planning a 600-satellite-strong LEO Outernet constellation also expected to begin launching in 2025.

“While it has first mover advantage as an ISP using LEO satellites, there will be others that ultimately will give Starlink a run for their money,” he adds. “The ISP business is a difficult one where margins are very slim, if positive at all, and the projections made by Starlink back in 2019 – to achieve $35 billion in five years – have been missed in a big way.”

At Marlink, LEO integration was key to rolling out a complete set of connectivity services including cloud, cybersecurity, and IoT.

“Marlink is already in conversation with Kuiper and Telesat about the services they will offer in future, because the more options we can provide the better for our users,” Van der Breggen says. “When those services start to arrive in shipping and energy, the questions from buyers will be how they compete on price and service quality. Just like consumer markets, maritime and energy are highly competitive so the impact can only be judged for real once the services are available.”

Kuiper’s chances

With the benefit of hindsight, the Kuiper Project could achieve second-mover advantage, learning from Starlink’s mistakes and taking advantage of painstakingly established regulatory frameworks trailblazed by the pioneer to make for smooth sailing for a fast follower like Kuiper. Experts have agreed that the entry of a second billionaire-backed corporate empire could easily upend the emerging balance of market powers, if not represent a new monopolizing influence.

“Kuiper is mostly a me-too product and will probably not benefit from [studying Starlink’s fumbles],” Rivada’s Van der Breggen contends. “If differentiation is sought by Kuiper, chances are that it will be in the pricing.”

Kuiper’s aggressive pricing could dovetail neatly with the cloud services offered by AWS, Amazon’s market-leading public cloud platform, as well as the company’s consumer offering Amazon Prime.

There are already examples of companies wanting to take advantage of this. In September 2024, mining group Johannesburg-based Gold Fields said its decision to move to AWS was partly in expectation that the Kuiper system would integrate more efficiently with Amazon’s cloud offering.

“Amazon could offer their Internet access services [to the public] through the Kuiper constellation completely for free,” says Van der Breggen. “Anticipating that revenues through its website would increase by a couple of percent as a result, which would already make it worth it. Unthinkable? Well, don’t forget that Starlink started out subsidizing their antennas, only asking for a nominal amount.”

There are other participants in this race. The protectionist policies pursued by the US and other governments around the world could accelerate an existing trend in satellite markets for data sovereignty. Billionaires aside, international buyers may come to prefer or even require domestic options in connectivity.

So far, Kuiper has already signed deals with telecoms groups like Vrio, Vodafone, and Verizon for connectivity in broadband and mobility. In mid-February, it announced a £670,000 ($865,000) consultancy contract with the UK Ministry of Defence, studying the potential for “translator” satellites to facilitate orbital communication between military, government, and private satellites.

Another noteworthy interest has emerged from the Taiwanese government, which confirmed talks with the Kuiper Project in December 2024. The nation has long seen a decisive strategic advantage in access to LEO constellations following news of the use of Starlink in the war in Ukraine could be limited, and has sought orbital communications support to augment their defense in the case of a Chinese invasion.

Since early 2023, Taipei has stated a desire not to “tie ourselves to any particular satellite provider,” but rather work with as many as possible to achieve better resilience, all but guaranteeing its interest in Kuiper.

Small-tech competition

“While the business hasn’t traditionally boycotted providers based on their nation, securing connection and security from the right allies as part of data sovereignty most certainly has,” says Rivada’s Van der Breggen. “The ability of various satellite service providers to support and fully control the flow and location of data does sway enterprise and government users to make drastic decisions as to who to choose as their data communication service provider.”

Van der Breggen explains that Rivada stood to benefit from this trend. Being an operator founded in Germany, with offices in Berlin and Munich, could ensure uptake of German LEO demand. The appetite for an alternative to Starlink in Germany could be high following Musk’s attempts to intervene in the recent German general election, which saw him voice his support for the far-right AfD party.

Rivada’s multi-node network approach allowing full mesh rooftop-to-rooftop connections for government and enterprise means the company is “not so much guided by what Kuiper or Starlink are doing, as they cannot offer these types of services,” Van der Breggen suggests.

Many legacy providers also tout this sense of know-how in delivering bespoke connectivity, emphasizing their diversity of technologies and decades of experience serving industries.

Starlink appears to believe in the latter, given its tactic of reselling services through many existing network providers, and selling capacity into competing networks with pre-existing connections to unfamiliar but lucrative markets such as those in Asia. Since the latter half of 2022, Starlink has been working partners such as Speedcast, SES, KVH Industries, netTALK maritime, Singtel, Tototheo Maritime, and, of course, Marlink, in shipping alone.

For now, this tactic appears to have sold capacity while spreading the Starlink name without an overwhelming marketing burden, nor having tailored their offering with advanced customer relationships, leaving the hard work to the networks being partnered with.

We may see Kuiper do something similar, though its exact path and how successful it turns out to be could hinge upon how it navigates 2025.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 56 of the DCD Magazine. Read it for free today.

Read the orginal article: https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/analysis/on-the-cusp-of-the-kuiper-campaign/