Though we live in the age of silicon chips and fiber optics, copper ran the digital world for decades. Thousands of miles of copper and thousands of exchanges dot the US, soon to be retired for more modern technologies.

The telecoms companies of the world may be retiring their copper networks in lieu of fiber, but the real estate footprint of yesteryear’s networks still has something to offer.

US telecoms firm Ziply is launching a colocation business based on a footprint of aged telecoms assets the company inherited.

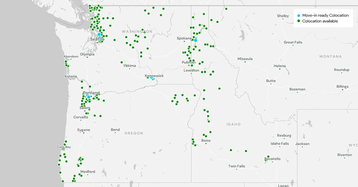

The company’s new data center network, totaling more than 200 facilities across Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana, is based on the firm’s footprint of copper network Central Offices that, in some cases, date back to the swinging sixties.

A local Internet service provider (ISP), Ziply Fiber is dedicated to bringing fiber Internet to Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. A subsidiary of private investment company WaveDivision Capital, the company was formed by former Wave Broadband executive Steven Weed in May of 2020 when it acquired the Northwest operations of Frontier Communications. Ziply has since been acquired by Bell Canada.

Ziply’s history meant it was well-placed from an infrastructure point of view. As the successor to General Telephone Company, it inherited many of the Central Offices from the carrier’s days as the incumbent local exchange carrier (ILEC).

ILECs were local telephone companies that held the regional monopoly on landline service before the market was opened to competitive local exchange carriers (CLECs) in 1996.

Central Offices, also known as telephone exchanges, were long the key switching points for the old telephone networks. Telecom companies across the US had thousands of these sites, which vary in size depending on the area they were built to serve, that have become increasingly underutilized as carriers switch to fiber networks.

But these purpose-built facilities – constructed in phases from the 1950s to around the 1990s amid the days of DSL Internet – represent a largely untapped resource for telecoms companies, offering carriers a chance to create a new fleet of data centers as the switch from copper networks to fiber continues.

Ziply’s facilities are largely centered around Seattle, Portland, Kennewick, Boise, and Spokane, but stretch to locations across Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.

“We have buildings that go back into the 1960s on a pretty regular basis, and we have ones that were built in newer periods up to the mid-1990s and the dial-up modem revolution,” says John van Oppen, VP network, Ziply Fiber. “In that period, a whole bunch more sites were built or expanded, because they had to handle more phone lines after everybody went from one phone line at home to two or three, and so that was a massive expansion in infrastructure. Then DSL lost to cable, and the space has mostly been sitting underutilized since then. That left us with a big opportunity once we started decommissioning equipment.”

From GTE to Ziply

Ziply’s network has its roots back in the General Telephone Company of the Northwest, Inc. which was founded in 1964. Later known as GTE Northwest, the company was acquired by Bell Atlantic and became Verizon Northwest. After being acquired by Frontier in 2010, it became Frontier Northwest.

Following its acquisition and rebranding to Ziply, the company said it would invest $500 million in improving the network and upgrading from copper to fiber, before raising another $450m for further network expansion. The repositioning of these Central Office sites for data center use came as a natural follow-on from the network upgrades.

“We knew what was in there, as far as old telco gear, but our vision was to build out a modern fiber network, so we understood that so much of that equipment would be decommissioned,” says Chris Gellos, GM/VP commercial, Ziply Fiber. “It’s really been a neat project for us to follow on top of the modernization of the network and our central offices to operate our network, to now jump into this more customer-facing project and providing colocation.”

The facilities were previously filled with large amounts of equipment for the company’s old copper network. A lot of that was ripped out and replaced as part of the network upgrade program, leaving plenty of newly created space for the company’s colo business.

One site, van Oppen notes, once peaked at 98,000 phone lines. Today that building has capacity for 75 racks and some 500kW of unused power now the switch has been decommissioned.

The company hasn’t shared an official number of the total capacity of the sites, but Ziply tells DCD it is “many, many megawatts,” with the largest site totaling just under 100,000 sq ft (9,290 sqm.)

“There’s four or five sites that have more than 1MW available; probably 30 or 40 that have somewhere between 500kW and 1MW available; and there’s a whole bunch – hundreds – that have around 50-300kW available,” says van Oppen.

The company hasn’t officially priced the assets, but told DCD the replacement value would be “several billion dollars.”

“This is a uniquely ILEC footprint,” says van Oppen. “You wouldn’t have built them for a newer world, unless you were building colos.”

The company spent months ripping out phone switches and the ladder racks, taking the spaces back to largely empty rooms with 18-20ft (5.4-6m) ceilings that can be configured to the customers’ needs.

“After pulling out the gear, we take a look at what space is available in the building, and then we figure out if we need to rip out ladder racks, ducts, or whatever was configured the way we decided wasn’t acceptable for colo, and shuffle it around,” says van Oppen. “Then you install UPSs, you install new air handlers.

“Our planning is driven by what we think we’re going to sell; how many watts per square foot, how many watts per rack. We have this great shell that has power, diesel storage, and network, and then you reconfigure the inside of it to fit a different type of layout than it was previously used for.”

Each site generally has an A-B electrical feed (or A-B-C in some cases), along with several days’ worth of fuel storage. Like Cogent’s project, the sites largely run on -48v DC power. The company is undergoing some retrofitting work; some carrier customers want DC power, but most want AC power.

“Our big retrofit challenge has really been to make AC power available in these sites,” says van Oppen. “And we’ve been doing that in a combination of a preemptive basis and an ad hoc basis.”

That the sites are all already permitted and stripped back means that there is a lot of immediately available capacity.

Though some of these locations date back to the days of Little Richard or the Beatles, there’s scope to add new buildings in some cases. While the company will initially focus on using the already authorized but underutilized load it has been allocated, the company suggests there is also opportunity in increasing capacity to existing sites, which avoids some of the delays of new grid connections.

“We own something like 400 buildings, and we own the land, and it’s fascinating to me to see what’s possible,” says van Oppen. He says that one CO was in a position where there was enough land to double the size of the facilities, without eating into the number of parking spaces.

“We’ve looked at a couple of sites and realized that we could get to 5-10MW without too much trouble and without spending a ton of money with utilities,” he adds. “We also have a number of sites that have megawatts of unused electrical service today.”

Cold War thinking for 2020s resilience

Today the company has some 30 people on the facilities team. Outside contractors do a lot of the building out of space, but the maintenance – including of HVAC and generators – is done in-house.

“If there’s a refrigerant leak, it’s our guys that go fix it,” says van Oppen. “If a generator doesn’t start somewhere, our diesel mechanics take it personally checking to see if it was their part that didn’t work. And that kind of culture is super important to create for reliability.”

The way the COs are set up also helps ensure reliability. In November 2022, a winter storm hit Snohomish County, just north of Seattle, leaving nearly 200,000 without power. Power cuts in the area lasted five or six days in some cases.

“Our buildings, more than the typical data center, are actually structured around almost Cold War resilience,” says van Oppen. “We’re in hardened traditional telco fortresses; all of our sites have at least five days of fuel. We joke that we will be the last one standing in these markets.

“We had nine or 10 sites on generators for that whole period,” he adds, referring to the 2022 storms. “By day five, we said we should probably order some diesel to this site.”

While Ziply’s sites were all up and running, the driver of the refueling truck could only report in from the COs, as their cell phone carrier was backhauling via a different provider that had gone offline.

“Our biggest failure in that scenario was our third-party cell carrier, who since switched a number of those towers to us,” van Oppen beams.

In a post to LinkedIn in early December 2024 following bad weather, van Oppen noted that more than 20 Ziply sites in the Seattle region were running on backup power for more than 36 hours without issue.

Colo and carrier thinking

The company launched with around eight of the 200 facilities listed as “move-in ready” – with racks, HVAC, and UPS installed and ready – and had some customers in place at launch. Word that Ziply was planning to offer colo had gotten out, and some interested parties reached out before it officially launched to place hardware in the old COs.

“It had an organic start, even though we had already planned to go in this direction,” says Gellos. “They came to us and we met their needs.”

Early customers included local businesses – so-called server huggers who like to be close to their hardware – local governments and other carriers. Ziply believes the sites “fill a gap” for retail colo customers struggling to compete for space against AI customers.

“We’ve been watching AI users displace all the normal colo users, because we’re in a unique position to help them solve for connectivity and space and power problems,” says van Oppen. “They have been pushed out of or priced out of the retail market as operators have gone to selling their power to a few big customers. I think there’s a really big niche there that folks can use us for.”

One of the major early deals was a government customer that wanted a custom deployment with a lot of battery runtime as part of requirements described by the company as “not normal.” Van Oppen notes, however, that it was “easy” to meet these demands.

“We had a big site that fit the requirements where they wanted it, and had a ton of empty space from all of our cleanup efforts,” he says. “We had so much empty space, my team was using it for storage and had bought a forklift for the site.”

That deal was something of a surprise for the company.

“One thing that we learned in this is that we’ve had some of the most interesting opportunities on sites we didn’t expect,” van Oppen adds. “That site wasn’t on the list originally, because we thought nobody was going to want colo in that town. And it turns out they do.”

Another named customer is Scatter Creek InfoNet, a family-owned broadband provider to Washington’s Tenino and Kalama areas. The firm is now leasing out of Ziply’s Somerset West Central Office in Hillsboro, Oregon.

To date, all of the deployments have been air-cooled, with the company generally supporting averages of 5-7kW per rack but seeing densities up to 18kW in some cases. But van Oppen says Ziply has received some interest in liquid cooling – some of its sites already run chilled water loops, which could lend themselves to liquid-cooled systems.

Van Oppen notes that Ziply itself is a customer of a lot of colocation providers on the network side, and while Ziply “works well” with them, he sees the pain points of being a customer and is trying to do things differently. At the same time, the company wants to “behave more like a colo operator” than the incumbent carrier.

“We ask ourselves, how can we be a friendlier vendor than our own customer experience with the large carrier facilities?” he says. “Most data centers won’t do deals past five years. And if you’re a network service provider, you really want long-term assurance. Because we own the buildings, we can do longer-term deals on those. And that’s what’s really important to making the sites into an anchor.”

The company’s fiber network connects to data centers from major providers in its service region, including Sabey, Digital Realty, Flexential, H5, NTT, Vantage, Cologix, TierPoint, Evoque, and others. The connectivity options for its CO sites are a major selling point for Ziply – with the company hosting multiple carriers in many of the facilities.

“Some carriers have stripped Central Offices out of their assets. We’ve made a conscious decision not to because we think they’re most valuable when combined with the conduit assets,” says van Oppen.

“We’re not a normal colo provider in the traditional sense, because a colo provider wouldn’t be able to sell you conduit down the street. We can pull you a dedicated cable the entire way through existing conduits between two of our buildings. If you wanted your own private ring, you could have that. I’m not aware of any colos that are able to do that, beyond their own campus. And that’s the difference between being the carrier that also owns the conduits on the street and being a colo provider.

“And that kind of feature set is the kind of stuff enterprise customers are asking for these days; how do I get private, fully protected, redundant infrastructure?”

The company has also donated fiber and space to the local IX, NWAX; a nonprofit Internet exchange in Portland, Oregon, that has placed a switch in one of Ziply’s sites.

“We acquired the old phone company assets, but we are not the old phone company, by any means,” adds Gellos

Read the orginal article: https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/analysis/copper-to-colo-ziplys-plan-to-repurpose-its-central-offices/